"We are the fourth generation born and raised in the camp," Hamdih tells us. He is a craftsman and builder, but has lived in Italy for years and now he is our translator and guide. Dheisheh camp, at the gates of Bethlehem, Ibdaa center. We are on the other side of the wall, the eight-meter-high concrete wall we walked through yesterday.

"Our grandparents came here from the towns and villages conquered by the Israelis in 1948. Back then they lived in tents and every day they had to stand in line in front of the Unrwa (the UN refugee agency) office to get something to eat. Since then we have remained in the same condition: refugees."

Today there are no more tents, in their place have sprung up houses that grow by one floor when an extra apartment is needed. After all, Palestinian builders and craftsmen are the most in demand in the Middle East, even by Israelis.

The camp's contacts with international solidarity are made as early as the first Intifada, the popular uprising of 1987.

In 1994, the Oslo agreements promised autonomy to the West Bank and Gaza, raising hopes that a Palestinian state could be achieved. It all turns out to be a tragic deception; settlement construction and occupation continue. In 2000, the second Intifada breaks out, the Dheisheh camp is again invaded by the Israeli army. The presence of several European soldiers helps to limit the violence, but in fact it is the end of the hopes of the 1990s.

Dheisheh, like all other refugee camps, remains under the care of Unwra, which provides basic services and delivery of food parcels, but does nothing to support the autonomy of the population. The goal is to maintain the status quo. Other funds come from the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), which is governed by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and with that money and the support of international solidarity, the camp committee (elected by the residents) has carried out other projects. "We did the sewage," says Mahmood, among the committee members. But all this does not change the condition of the camp residents. They can move freely only as far as Bethlehem, which is located in so-called Area A, the one under military and administrative control of the PNA.

Farther on begin the checkpoints of the Israeli army, which can close them at will. Area A is in fact a collection of towns and villages without territorial continuity, surrounded by areas B (Israeli military and PNA administrative control) and C (Israeli control both military and administrative).

In Dheisheh 65 % of residents are unemployed, those who work in many cases do so in Jerusalem, in the territory of the State of Israel.

To go there you need a special permit from the Israeli army, granted only for work purposes. It is valid only for the hours and place of work and is renewed monthly. The employer can have it revoked at any time. Every day hundreds of thousands of Palestinians return to the territories from which they were driven out as highly extortable labor.

Hamdih and Mahmood guide us through the alleys of the camp. It occupies an area of 1.4 square kilometers and about 15,000 people live there. On most of the houses there are portraits and graffiti in memory of the martyrs. There is also a small monument in their memory.

Red flags of the Marxist-Leninist-inspired Popular Front For the Liberation Of Palestine (FPLP) fly at street intersections and on the homes of those who have emerged from Israeli prisons. More rare are the yellow ones of Al-Fatah.

The camp is a stronghold of the Palestinian left. The PNA's ultra-moderate leadership does not seem to get much support around here.

When we arrived we saw a burning dumpster in the middle of the street, the way of the camp youth to protest some arrests made by PNA policemen for political reasons and demanded by Israel. Arrests made outside the camp, inside would not have been possible because of the resistance of the population. "We had clashes with the police even when the Pope came, because they would not allow us to greet him. Their barriers could only take them back after two months," Hamdih laughingly tells us as he accompanies us. He shows us a second cultural center, complete with a library and gymnasium for women.

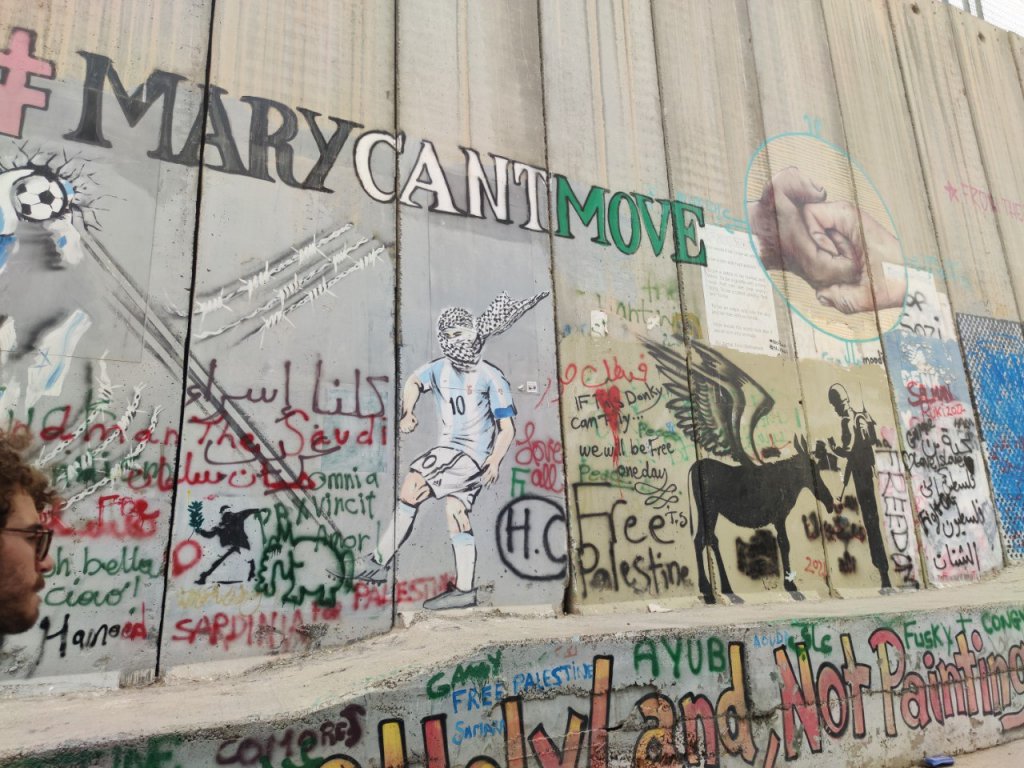

After the tour of the camp we head to Bethlehem. The first stop is at the Apartheid Wall.

The only beautiful thing about this concrete and barbed wire monster barring the horizon are the many graffiti and messages of solidarity spelled out in all the languages of the world.

Just a couple of kilometers away from the wall and we find ourselves surrounded by souvenir stores and tourists, we have arrived in the center of Bethlehem, close to the Basilica of the Nativity.

In the evening Hamdih invites us to dinner, and in between chatting and grilling he and his friends teach us a few steps of the Dabke, a Palestinian folk dance. The same one banned in Gaza by Hamas Islamists because it is danced together by women and men. The attack on Palestinian identity comes not only from Israel.